I came to the UAE after living, studying and working in South Yorkshire for years.

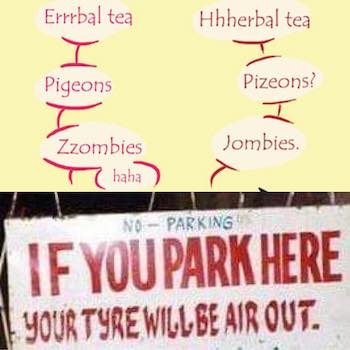

Yorkshire lingo is a class apart from proper British English. On my first day as a student, a shopkeeper greeted me with “You ok, love?” and “Good day, duck”. I could not follow his accent and he obviously did not stock okra in his pristine store, so we had a mutually unintelligible conversation. But James Herriot’s favourite folk are so friendly and down to earth that I was soon using “You ok, mate?” with gusto.

When I returned to the Middle East, I realised that my roots had become tousled by my life in Britain. Catching up on the Indian English used in Dubai was hard. ‘Yaar’ and ‘da’ made me cringe.

My dad once scolded me for calling my best friend Heena, “yaar”. I owe my language skills to him, as he wanted my brother and me to learn at least one English word a day; i.e., its meaning and pronunciation. Then I went to Kerala and learned the Malayalee way of speaking English. No offence, but it was ‘simbly’ great. I love Kerala, so I was soon imitating the Malayalee way of talking, with a passion that would put any sane native to shame.

In India and among most Indians living worldwide, we have our peculiarities – especially noticed by my BBC colleagues, whenever we interviewed Indians on the street. We happily call everyone from auto drivers to waiters to friends, “Uncle, Aunty, Bhai, Anna, Chetta, Macha, Aliya or Boss’. We may not call our actual bosses, boss. We knight them and ‘Sir’ them. Anything not funny, we call it a ‘poor joke’. If anything is good, it’s ‘first class’ for us. Or ‘Ek dam first class’ – not swearing, it just means absolutely top notch – it can’t go higher than that in India.

Our names are not merely names, but ‘good names’. If we ask you to ‘sit’ it’s rude, so we say, ‘sit, sit’, so we don’t seem stern. I love the respect that we Indians give to our elders, so I stick to calling the older generation, ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’. No calling elders by their first names in my country, thank you. We don’t advance, we ‘pre-pone’. If you have ‘passed out’ of college, that’s cos you were ‘mugging’ (not a criminal activity – that’s how we refer to students cramming for their tests)

If you get too fond of a culture, you tend to pick up some of its lingo. But you should stick to English words and diction when you speak English. And when you speak your mother tongue, proudly speak it like how you speak it to your mother at home. We don’t need English accents for our mother tongues. Indian local language newsreaders should keep that in mind.

India can be proud of the fact that even the country’s school dropouts can speak basic English (My super-proud-Indian-self is spontaneously bursting with pride) But we Indians do bring an Indian touch to the English language and an English touch to our mother tongues, which might exasperate a foreigner. Indians change “choti choti batein” or “kochu kochu karyangal” or “chinna chinna pesu” to “small small things”. Similarly, “I ate it fast fast” is a translation of “vegam vegam”. “Fan on karo” is literally translated to “On the fan” instead of “Switch on the fan”.

Indians prefer to say that things are “Going on” which comes from “Chal raha hain” or “Angane pokunnu”. It takes years of teasing to get rid of it.

Indians add “basically” or “actually” to most sentences they speak. That’s “Dar asl” turned English, I guess. Children tend to say, “I am having a class tomorrow”. If you are “having a class” (present continuous), you are probably having it now. Tomorrow, you would “have a class”.

Another added Indian touch is “itself”, “myself” and “only”, “Na” which confuses many of my British friends. One of my finest journalism tutors and one of the most meticulous editors I have ever known – Mr Jyoti Sanyal – had pointed out that in Malayalam, one adds “thanney” (itself, myself) to sentences. He got those out firmly – out our systems and our lives – when we were his students. For e.g., one says “Njan thanney aanu avide poyathu.” That’s polite in Malayalam, but its literal translations, “I myself went there” and “I only went there”, sound terrible. “I went there” would do.

And if you have the tendency to add “No” to the end of every query, chances are that you have got it from the Indian queries “Aap theek hain, na?” or “Sukham thanne alle?” which you change to “You are alright, no?” instead of a simple “Are you alright?”. Another frill is “also”. That comes from “koode” in Malayalam and “bhi” in Hindi. “Athum koode vayikkuka” or “Who bhi pado becomes “Read that also”. The word “different” is used to mean “various”. You have “various” hobbies, not “different” hobbies, even though those might differ from each other.

We Indians tend to pronounce certain words wrongly too. Police becomes Polis while it should be pronounced Poleece. Gas is gas not gyaas. Cucumber is kyukambar not kukkumbar. Kangaroo is kaangroo not kangahru. Garage is garahj, not gyaaraij.

If you are an Indian speaking in English, be proud to speak it in whatever accent you are comfortable with – British, American or Indian, but remember to pronounce the words right. And speak Indian languages the Indian way. God forbid that we destroy India’s rich languages with a fake foreign accent.

Like they say, may one never become an Indian who is more Western than natives.

By Linda Joseph Kavalackal,

Editor-in-Chief,

Christ & Co.

Thank you for sharing such a heartfelt, intriguing, “Ek dam first-class” article that speaks to the importance of preserving our linguistic heritage around the world. God bless!

Thank you, Darryl for that ‘Ek dam first class’ comment and your kind words!

and your kind words!

God bless.

I was exploring on line for some information since yesterday night and I found this! This is an excellent website by the way.